A version of this story originally appeared on Baltimore Beatdown on Jan. 16.

As flood waters rose in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, 12-year-old Arthur Maulet and his grandfather escaped their home by splintering a hole in the ceiling with an axe and climbing onto their rooftop. From there, they waded through the floodwaters to the Claiborne Bridge and awaited rescue.

Hurricane Katrina had made landfall East of New Orleans and the levee walls protecting the city broke. Devastation surged into the streets and murky waters filled the two-bedroom home that Maulet and his grandfather, Anthony Hicks, had make-shifted into a five-bedroom to fit Maulet and his four siblings. His sisters, Kawanda and Bri, slept in one bisected room while he and his brothers Juan and Henry shared the other. Hicks slept in the living room. But none of it mattered as they sat on the Claiborne Bridge.

Eventually, a National Guard helicopter whirled above them and Maulet and Hicks were saved from one of the deadliest hurricanes in United States history. They were flown to the Superdome, which was operating as a refuge center.

For two weeks, a young Maulet saw the horrors of Hurricane Katrina. Now a fierce 30-year-old competitor and a physical cornerback in the NFL, Maulet shifted uneasily in the Ravens locker room recounting the trauma.

“Women getting raped. Kids getting raped,” Maulet said. “People getting killed. People dying. People fighting for food. It was … it was a shit show. I was lucky I wasn’t there long enough to be in one of those situations.”

Maulet, Hicks and a few of the children returned to their home a month after their refuge in the Superdome, or where it was. The home, like countless others in the Ninth Ward, was gone. Any possessions the young boy had were swept away in the destruction. The only distinguishable features of where they lived was a painted outline of the hopscotch drawn into the concrete sidewalk. They also found the fish tank Hicks kept with fish named after all the children, alive and swimming in the tank.

“What are we gonna do with your fish box,” a grandchild asked Hicks.

“We don’t have nowhere to live,” Hicks said. “We can’t provide for the fish no more.”

The sight of his home swept away in the surging water stunned the adolescent Maulet.

“For me as a kid, I was kind of still young and I was helping build on the house. And I was like, ‘Damn. Everything that we worked for, built for, to kind of be comfortable with all these people in the house was gone,'” Maulet said.

Hicks took the family to Texas for a short stay as he tried to figure out their next move. Then, a Presbyterian church reached out with incredible help, funding a home in Ann Arbor, Mich., for the six of them to live.

But that was just the start of Maulet’s nomadic journey to the NFL.

Our insiders, Garrett Downing and Clifton Brown talk with Arthur Maulet after his new two-year contract, and he discusses why he’s confident this defense will build off their great success in 2023.

Listen On Apple Podcasts

Ann Arbor & Georgia

Hicks and the five children arrived at a home in Ann Arbor that brought joy to the family. They had enough bedrooms for a boys room, a girls room, and Hicks had his own. Maulet smiles, revisiting the memory.

“We had a big yard,” Maulet said. “It was my first time shoveling snow! I was like, ‘Yo, this is pretty cool.'”

It was in Ann Arbor that Maulet discovered his love of football and sports. Maulet received tickets to see the Michigan Wolverines in “The Big House.” Afterward, Maulet enrolled in basketball in the winter. In the spring, he played baseball. The following fall, he played his first season of football.

For two years, Maulet enjoyed Michigan. He had a home that didn’t need Hicks and himself to continuously repair. He was safe and happy. Coaches were mentoring Maulet and volunteering to take him home from practices as Hicks was working to provide for the family of six.

But it didn’t last.

Hicks was summoned to the church’s office. The funds paying for the home had run out and they had 60 days to vacate. Maulet and his siblings were devastated.

Maulet struggled leaving Michigan. The friends he made and the security he felt were stripped from him. The family packed up and moved to Columbus, Ga., to live in a home provided for Hicks and his siblings by his uncle. No longer could Maulet play sports. He was thrust into a position to provide for his family.

After school and on weekends, Maulet wasn’t tightening his cleats or snapping on his chinstrap. Instead, he was leaving the house with Hicks to do odd jobs.

“We had to do plumbing jobs. We had to do roofing jobs. We had to do construction,” Maulet said. “I was the ‘next man up’ in the household.”

One particular job had Maulet and Hicks repairing the roof of a house. Hicks recalled how frightened the teenager was.

“Pops, I’m scared,” Maulet told his grandfather.

“Well, if we don’t finish this job, we don’t eat,” Hicks answered.

Upon completion, Maulet told his grandfather nothing would scare him anymore.

The work and stress to help provide for the family became too much for Maulet. He was in pain and his judgment was clouded. As a result, in his words, Maulet began running with the wrong crowd. He dropped out of school and looked for a way – anyway – to be a participant in life.

For what felt his entire existence, Maulet was on the receiving end of life, always reacting to the latest news or situation, which frequented loss and suffering. He sought a way to feel control, but it was with the wrong crowd. Hicks saw the path his grandson was taking. If Maulet stayed in Columbus, he could end up dead or in prison.

“You’ve got to get out of here,” Hicks said to Maulet. “You’re not going to make it.”

Maulet was on the move again. This time, alone, back to Louisiana to live with his aunt.

Back to New Orleans

Maulet quickly returned to school football. It brought stability and joy to the 18-year-old junior at Bonnabel High School just outside of New Orleans and kept him off the streets. It had been so long since he stepped onto a field that he put his pads on backwards.

At an Under Armour camp, Maulet’s first snap at cornerback proved he was in his element as he snared an interception. But the highs of being a cornerback faded quickly.

“He started roasting me after that,” Maulet said, laughing. “Throwing at me every time. Just darts. Catch, catch, catch. I’m getting mad.”

Though Maulet was allowing catches, he contended with each snap, catching the eye of defensive backs coach Donald Cox, who worked with numerous NFL players, including Keenan Lewis and Kendrick Lewis. The two formed a bond as Maulet showed the athleticism and competitiveness to be a legit player.

Cox coached Maulet his junior year, in which he made significant improvements by season’s end. Maulet was grinding workouts preparing for his senior season, a time when he expected to get the recognition he’d earned. That is, until he became ineligible to play due to turning 19 years old.

Football was Maulet’s driving force. With it stripped away from him again, he once more was without purpose. He quit living with his aunt. He was homeless and back to “bull-crapping,” as he puts it, on the streets. There was no way he was making it.

Weeks into being homeless, he decided to attend school one day. Cox found him and pulled him to the side with a plan devised to get him back on the right track.

“I told you, work your butt off for six months and we’re gonna go to a junior college,” Cox told him.

Cox brought the teenager into his home, and they got to work.

At 6 a.m., Maulet was at a 24-Hour Fitness going through workouts with Cox. Afterward, he studied for his G.E.D. After finishing his studies, he went with Cox to his new coaching gig at Helen Cox High School, where Maulet helped coach his peers. It fueled his drive, seeing other athletes practicing while he was unable to play.

After six months of workouts, studies and sitting on the sidelines, Maulet and Cox’s plan worked. He earned his G.E.D. and was headed to Copiah-Lincoln Junior College for a tryout.

Mississippi to Memphis

It wasn’t easy at any stage of Maulet’s life, so of course his JuCo tryout wasn’t any different. As Maulet stepped onto the grass, rain began to pour in Wesson, Miss.

“What the hell,” Maulet asked to the sky above. “One more thing, right?”

The team had four spots on defense that could be given to an out-of-state player. Maulet noticed in the locker room as they were putting on their gear for the tryout that his top challenger was getting new pads. Meanwhile, Maulet was tightening frayed straps and worn plastic shells on his shoulders. It poured more jet fuel onto Maulet’s fiery spirit.

Tryouts concluded days later, and Maulet was informed he made the team. He overcame being a player with no senior film and hadn’t suited up in over a year.

Maulet didn’t play much in his freshman season but the year of being on a team and granted access to coaches helped launch him into a dominant sophomore year. In 11 games, Maulet racked up 30 tackles and five interceptions and a pick-six at cornerback.

It translated into more than 20 offers from colleges, where Maulet selected the University of Memphis. But like everything else in Maulet’s journey, it wasn’t so simple.

Maulet didn’t have enough credits to be allowed to play football in the spring, when he accepted the offer. He couldn’t get housing, either. Maulet’s only option was to stay at his friend ‘Smacks’ house on the couch while he toiled away gaining college credits.

Maulet was back to solo workouts, keeping his body fresh for what was to come. Once he was back on the field, Maulet was overmatched in fall camp and his first season at Memphis.

“It was the worst,” Maulet said, shaking his head.

Maulet was, well, bad in his first year at Memphis. He allowed the second-most receiving yards (866) among all FBS cornerbacks in 2015. He allowed the second-most touchdowns (eight) of any FBS cornerback.

Maulet maintains he’s a realist. When he’s good, he allows himself to know he was good. But when he’s bad, he doesn’t shy from his own critique.

“You suck,” Maulet told himself at season’s end. “You got to get it together or you will not be doing nothing, man. You won’t be going to the league.”

The self-flagellation spurred his spring and summer workouts. He was a man possessed to improve. Self-imposed two-a-day workouts all year long proved bountiful when Maulet returned for his senior year.

Maulet became a force in his senior season. He finished as the No. 10 cornerback by Pro Football Focus’ coverage grade, narrowly beaten out by first-round cornerbacks Tre’Davious White and Marshon Lattimore by a fraction of a point. Maulet stuffed the stat sheet with 59 tackles, five sacks, two forced fumbles and two interceptions. He slashed his yards allowed by more than half, allowing only 418 yards. He allowed two touchdowns all season.

He was ready for the NFL. All that stood before him was the NFL Scouting Combine.

A New Home in the NFL

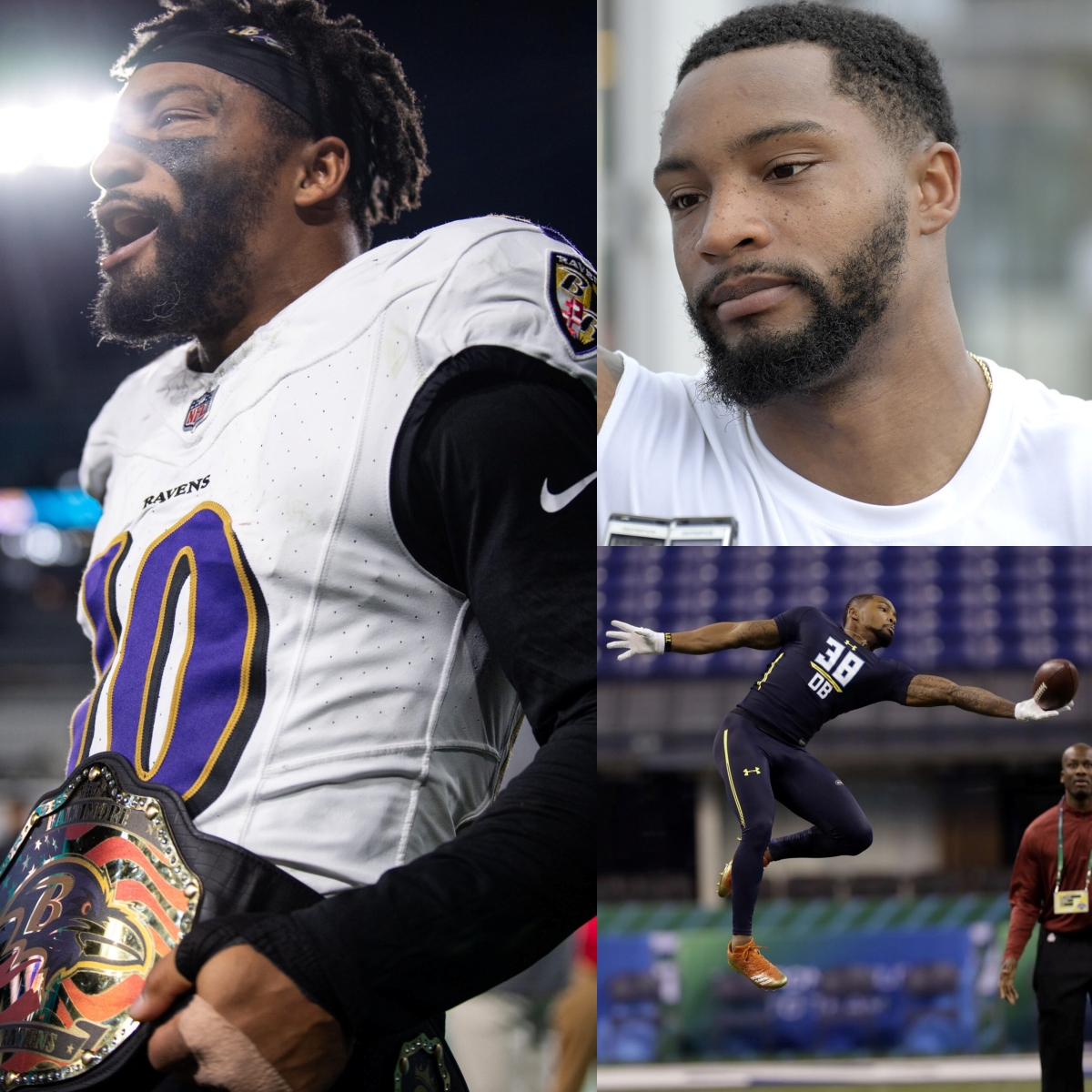

Maulet had the production to be drafted, maybe even on Day 2. But the game film isn’t everything, hence the NFL Scouting Combine, where sprinting in shorts can make or break a young man’s future.

Maulet did everything he could to avoid his career collapsing before it had started. He saved enough money to pay for training by specific trainers who specialized in shaving down 40-yard dash times, and even flew to San Diego to get it, but never got the trainer he paid for.

Maulet got a last-minute invite to play in the Senior Bowl, but his helmet and pads didn’t arrive. He was forced to wear kicker Jake Elliott’s helmet for the game. Players were laughing at Maulet when he put on the two-bar helmet and stepped onto the field against Eastern Washington wide receiver Cooper Kupp and East Carolina wide receiver Zay Jones.

On Maulet’s first play, Kupp ran a double-move and Maulet’s sticky coverage broke up the play. Late in the fourth quarter, however, Jones caught a 6-yard slant for a touchdown against him.

Fortunately, Maulet still received an invite to the NFL Scouting Combine in mid-February. It all came down to the 40-time.

“Just run a 4.5, bro,” Maulet remembers everyone telling him. “Just run a 4.5 and you’ll get drafted.”

Maulet gave it everything he could and looked at the clock.

4.62 seconds.

He returned to the blocks. Second chances are familiar to Maulet. Each time he’s been given one, he’s run with it.

He sprinted another 40 yards and looked up at the clock. He couldn’t believe it.

4.62 seconds.

“My journey was just so much. I feel as though I could have run faster, but I just was going through so much, bro,” Maulet said. “My heart’s broken. That’s it for me. Priority free agent.”

Call it hope or optimism. Call it being a glutton for punishment and denial. Either way, Maulet still held a draft party in hopes of experiencing the happiest day of his life with his friends and loved ones.

They all sat down at Ubee’s in Memphis in hopes of watching one of the best FBS cornerbacks find his NFL home. But what followed was heartache as he watched 253 players be called, none being him.

Maulet watched his teammate, Elliott, get drafted by the Cincinnati Bengals in the fifth round. He knew it was over for him when University of Houston cornerback Brandon Wilson, a player from his conference, was drafted by Cincinnati.

After the draft, Maulet’s phone began to ring, including a familiar 504 area code. The New Orleans Saints, his hometown team, wanted him.

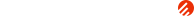

Maulet’s NFL experience is parallel to his life’s journey. He’s played for five teams, traveling from New Orleans to Indianapolis, New York (Jets), Pittsburgh and now Baltimore. He hasn’t played anywhere more than two years.

That’s set to change in Baltimore after Maulet agreed to a new two-year deal with the Ravens on Tuesday. Maulet finally has a longer-term home.

He earned it as a hard-nosed and versatile nickel cornerback in Baltimore’s fierce defense last season. Maulet played in 14 games, made 37 tackles, one interception, two sacks, five tackles for loss, and two fumble recoveries.

Through it all, Maulet has a furrowed brow and a smile, ready for the next challenge but feeling happy and blessed.

“I feel as though I have more work to do,” Maulet said. “Obviously, I’m blessed to be where I’m at. I don’t really tell my story a lot. I don’t want the excuses. I don’t look at my faults or look at anything to pin my mishaps on. I look at it as learning lessons and keep moving.”