DAVIE, Fla. — Everyone close to David Long Jr. keeps dying. It’s morbid. It’s his reality. The 27-year-old linebacker grew to brace for bad news when the phone rings. The horror. The shock. The play-by-play accounts choked out by tears and heavy breathing on the other line. Always the faraway relative chasing a football dream, Long is forced to piece together grisly details through the frenetic voices of those living the heartache up close. A helpless feeling.

This phone call, however, was different.

On Monday, Nov. 9, 2020, at 7 a.m., Long headed off to work with the Tennessee Titans. He hadn’t even left his own driveway when his brother called to inform him who died this time. He felt nothing. The name was so outrageous, so nonsensical that David hung up without saying a word. Obviously, this was bad intel. Long drove right along to the Titans facility, took part in the morning team meeting and — upon sitting down in his locker stall — his phone started ringing again. This time, it was his sister.

He answered. She was bawling. The two didn’t need to exchange any words because, now, David knew it was true.

He cried in his locker. Teammates tried to console him. He headed into Mike Vrabel’s office. He sobbed uncontrollably. Long informed his head coach he needed to immediately drive 250 miles south to Atlanta to be with his mother. For 24 hours, family tried (and failed) to make sense of a senseless murder and, on Wednesday morning, Long drove right back to Nashville. The next night, he played in a prime-time football game against the Indianapolis Colts.

His brow furrowed. His heart pounded. He again harnessed all grief, all rage into his profession.

The moment should have broken him for good.

“All I see,” he recalls, “is red.”

This linebacker plays the sport the way Butkus and Nitschke and Lambert and LT intended. David Long Jr. travels from Point A to Point B with zero sensitivities, zero hesitancy and doesn’t tackle ball-carriers as much as he bludgeons them. He is a species going extinct. One of the last truly violent players in a violent sport.

That’s what brings Go Long to Miami Dolphins HQ. Many players are passionate, but Long sacrifices his body like his life depends on it. He begins by describing his game with two words — “on fire” — and assures there is a very good reason he plays with such wrath. He did not choose this profession because he’s good at it, no, there’s “a long story” behind Long’s play style and he believes it’s finally time to take a switchblade to those scars.

The SWAT team crashing through his home. The sight of life leaving his aunt’s face. The three cousins murdered while he was playing college football at West Virginia. The 2020 death that should’ve crushed his spirit.

All of this created a monster.

His blessing has forever been this curse.

He playsangry because Long sincerely has been an angry person. Long never toggled between dual personalities. Life experiences magnetically drew the Cincinnati, Ohio native to the most dangerous contour of a football field. At West Virginia, he was the Big 12 defensive player of the year. With the Miami Dolphins, he’s fresh off a career-high 113 tackles. If anyone can eliminate this team’s “finesse” label, it’s him. He picked the correct profession. No amount of flag-football propaganda or sanctimonious rule changes veil the unspoken truth that football is dangerous. Millions of people around the world are drawn to this sport because this sport is a collection of human car crashes. It is not for everyone. It’s for people like Long, who fearlessly hurl their body into harm’s way. People with demons.

The darker the demons, the scarier the linebacker. Many do self-destruct. Many cannot function outside of those three hours on a Sunday and the result is catastrophic. The best defensive players through NFL history tip-toe closer, and closer, and ever… so… closer to a breaking point without crossing the line.

Long has been walking this tightrope since the day he graduated from high school.

As soon as he gets over one death, another strikes. Then another. And another. To the point where everyone in the family asks, “Who’s turn is it now?” admits Long’s mother, Deon Joyce. On the field, the result is glorious destruction. Off the field, there’s a cost. He’s been strangled by survivor’s guilt. Every time he has every reason to celebrate, more bad news rips at any remnants of joy remaining. He grew up with 11 siblings in all, countless cousins, a father who was a pro boxer, a mother who worked nonstop, two brothers in prison 10+ years apiece all while carrying the 2,000-pound burden of being the man who’d give them all a better life. Personal bliss could come later. If at all.

“I wanted to get somewhere so bad,” Long says, “that it pissed me off that I wasn’t there yet.”

This burden only grows heavier. His roommate at West Virginia, Dravon Askew-Henry used to ask: “Why the f–k are you so mad all the time?!” Coaches, too. It was never anything they said.

Half of Long was present. Half of Long was attached to the trauma back home.

“As a football player, your life is violence. You hit. You hit,” says Long, smacking a fist into his other hand. “But you have to be able to balance that off the field.”

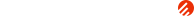

Rocking a bushy beard, cushy black slippers and sparkling earrings only trumped by an even brighter smile, Long insists he is a new man. Those closest to him agree. Still, uncensored anger helped create one of the best linebackers in the NFL. Right here is a player who represents the NFL struggle to its core.

Is a balance realistic?

“As you get older, you’re like, ‘Damn, why am I like this?’” Long says. “I sit back and reflect. A lot of shit happened for me to be who I am. I don’t let life make me turn sour.”

He pauses.

“I could.”

He can close his eyes and still see the red dots. Minuscule, haunting red dots through the back window of his mother’s Dayton, Ohio home in the pitch-black night.

Somebody was outside. Somebody was moving through the trees.

An eight-year-old David Long Jr. was sitting in the living room with his sister, Daeon. His two older brothers were with friends in a bedroom. His mother was working the late shift at General Motors. His eyes were no longer on the TV screen because those red dots in the backyard started to move. Two minutes passed, and… BOOM! The backdoor busted open. A voice yelled, “Get down!” and, for all David knew, these were coldblooded intruders.

He saw guns, hit the deck, closed his eyes.

“I don’t know what the f–k’s going on!” he recalls.

He was safe, but this full-fledged SWAT unit stormed into the bedroom to grab his two brothers: 16-year-old Keith Dewitt Jr. and 15-year-old Deandre Dewitt. The two were taken to jail for aggravated robbery with a bond set far too high for Mom to pay. While the brothers did commit one robbery in January 2005, the state tried to pin a slew of stick-ups in the area on them. Keith’s involvement was minimal. On the stand, one victim said he wasn’t even her perpetrator. Keith received two years behind bars, Deandre got 15 years and if that all seems steep, you’re not alone. These two had a different father. Keith Dewitt Sr. was a drug kingpin in Dayton, indicted and charged in 1999 for operating a cocaine and heroin distribution ring.

“It’d be like ‘Escobar,’” Long says. “If you’re the last name of somebody notorious, even if you got in trouble with the law with anything small, they’re going try to max it out.”

Adds Joyce: “They punished my kids for the sins of their father. They’d never been in trouble prior to that.”

When Keith Jr. was released, he got a job at the local automotive plant, enjoyed his freedom for about a year and then headed right back to prison for violating his probation. On March 27, 2009, he was stopped for a window-tint violation and that’s when police discovered a .380 caliber semi-automatic beneath his seat, a handgun that did not belong to Keith. The gun was already in the vehicle. Either way, he shouldn’t have been around a firearm. Back to prison he went. What should’ve been a short stay was extended when Keith got into a fight with a corrections officer. Extended, that is, by seven years. (“You have no idea what their name means around there,” his mother adds.)

The SWAT break-in scarred David. He was “pissed” and “sick,” but he was also exceptionally naïve. In his mind, Keith and Deandre would be home soon. A year? Maybe two? They were “King Tut” to him. Suddenly, he was the man of the house. David’s own parents had split when he was 2 or 3 years old and he moved with Joyce from Cincinnati to Dayton. Now, with Mom working the late shift from 3 p.m. into the night, Long Sr. distant and his two older brothers locked up, David never enjoyed a true childhood.

“I’m the man,” Long adds. “That’s how I walk, that’s how I talk. That’s how I attack my work. Because it’s me. I’m the one. I ain’t got time to bullshit.”

Thankfully, there was one more motherly figure in his life in Corrie “Nikki” Gooden-Long. “Aunt Nikki” had five sons of her own but viewed David as a sixth from birth. She, too, had no time for BS. She was stern, but damnit she raised all kids that passed through her home with 10x the love. Each summer, Aunt Nikki would take the whole crew on a trip. Sometimes, Gatlinburg, Tenn. Other times, Hilton Head, S.C.

Thankfully, he had football. Lack of size never mattered. All roughhousing with his older brothers sparked a temper that proved useful when he strapped on the pads. (“They use to torture me.”) Long can pinpoint the exact moment he announced the football field as his domain. The coach of the locally renowned Dayton Flames youth team, “Coach Dink,” pitted Long vs. one of the biggest kids on the team in a drill aptly called “Hamburger.” There’s no ball. No running back. No place to run or hide. The two laid on their backs, helmet to helmet, popped to their feet on the word “Hut!” and… Long destroyed the kid. “Smashed him,” he peacocks. “It set the tone.”

At 11 years old, he punked 14-year-olds on the Covington Bears, a team across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. (“Whupped their ass,” he specifies.) Legend quickly spread and coaches in Cincinnati tried to lure David back to his native city. One, Arthur Wilson, knew David Sr., and convinced David Jr. to make the 54-mile move south in eighth grade. Living with Dad didn’t pan out — he doesn’t offer further details — so son got creative by moving into a semi-abandoned Cincy home that belonged to another aunt who was off in Kentucky.

The place was essentially vacant. He and a cousin slept on air-mattress beds.

From here, he moved to another aunt’s house and lived with another cousin, Dante Jones.

Unfortunately, Long didn’t even make it to his third football game that eighth-grade season because he tore his meniscus. Mom was not thrilled. Mom wanted her son back in Dayton. But Mom also grasped the big picture. The fact that her son harbored dreams of playing college football was a good thing. After her other two sons were whisked away in cuffs, she vowed to do everything in her power to ensure David would not break the law. He’d play every sport possible because “idle time,” Joyce says, “is the devil’s workshop.” Wilson convinced Joyce to let Long live with him in high school.

To this day, Long calls this one of the best decisions of his life. He has no clue where he’d be if he went back to Dayton.

Urgency ran high that summer into his freshman year. Each day, he rode a bike 40 minutes to a Rivals camp in Fairfield in hopes of getting ranked.

“He was on a mission,” Joyce says.

Genetics helped. He was tough. After all, David Long Sr. was a heavyweight boxer who compiled a 12-5-1 record and earned the distinction of absorbing a KO blast from Deontay Wilder, a.k.a. “The Bronze Bomber,” and living to tell the tale. It’s a hard watch. Long absorbs a ruthless cross from Wilder in the 2011 fight, tips over like an oak tree chainshaw’ed at the stump and coils into the fetal position for a scary amount of time. Father and son have spent time sparring in the ring themselves and, today, Long loves boxing: Gervonta “Tank” Davis, Canelo Álvarez, Naoya Inoue are his favorites. Not that he needed to throw hands in the high school hallways — few dared to test him. Peers were naturally terrified. He got into two fights total.

Dad can take a kill shot from the future heavyweight champ.

Son can get hit by a car traveling 30+ MPH.

At age 7, Long Jr. hitched a ride on his brother’s Mongoose. Deandre was pedaling, while he balanced on the bike’s pegs. Down Salem Avenue in Dayton, the duo rolled along at a leisurely pace because they were joined by a few friends on foot. The group was safely in the shoulder the road. Long remembers a noise growing louder, and louder, until he turned his head and it was too late. He ricocheted over the windshield, straight up into the air and crashed to the pavement. To this day, Long is convinced the male driver was… uh… distracted. The last thing he saw was a female passenger leaned over.

He blacked out. His blood stained the street. Paramedics arrived and stripped him naked to locate all wounds. Says Long: “I was bleeding out.” Even then, even after waking up, Long couldn’t help himself. He wanted to pull a prank on these doctors. Inside the ambulance, hooked up to machines, Long pretended to fade in and out of consciousness like he had seen in the movies. Those doctors, reading his heart rate in real time, weren’t fooled. This is no mythology, though. Here, Long tilts his head down and parts his frizzy black hair to reveal a deep scar. Next, he points at two more pronounced scars on his lower left bicep. (“I can take a hit!”)

This was as close as Long ever got to trouble in the streets. Guns. Drugs. Robberies. The quick buck was never appealing because he had too much to lose. He witnessed the consequences of instant gratification firsthand. Brothers locked up. Dad with “four or five baby mamas.” Says Long, “I see something f–ked up and I just don’t do it. A lot of people make it hard. It ain’t.”

This blunt calculation instead steered Long to a hill in nearby Forest Park at 6 a.m. Basic ladder work wasn’t enough. He’d set the agility ladder up a steep incline and train until he puked, making it impossible for any coach to ever push him harder than he’d push himself. Work that led to a dominant high school career at Winton Woods — 283 career tackles, six sacks, six interceptions — and a coveted college scholarship. He was bound for West Virginia University. Donning a green robe and cap, Long accepted his diploma on May 21, 2015 and headed outside the arena to celebrate. He was hyped. He was happy. He posed for pictures with the same family members he’d give a better life.

Then, to his left, he could tell a few were distraught.

Pretending not to listen, Long overheard two words that’d change his life: “Which Nikki?”

During the graduation ceremony — inside her bed, at a sister’s house — Aunt Nikki had finally succumbed to pancreatic cancer. The family was trying to conceal the news from David because they wanted him to enjoy this milestone. But when one uncle heard who died and asked Joyce, “Which Nikki?” Long froze. Long blurted “Who!?” and, to this day, Joyce will never forget seeing her son’s complexion change on the spot.

Says Joyce: “The life left him.”

Long took off in a sprint. To where? Nobody knows. He thinks he ran toward the street. Or a car. All he remembers is that he needed to be alone. Three minutes felt like three hours as family members shouted David’s name.In hiding,Long replayed the last time he saw his bedridden aunt. Forty-eight hours prior, Aunt Nikki didn’t look anything like Aunt Nikki. Her face was sunken in. She had lost 50 pounds, minimum. And as David left her room, she howled in pain. A nightmarish whimpering scream that now rang through his head like a siren.

The reason Mom saw the life leave David’s face graduation day was he had just witnessed the same in Aunt Nikki.

“This is a woman,” Long says, “she’s been there. She was funny. She was a gangster. She was all in one. This was my first time realizing, ‘Damn, life is so short.’ It f–ked me up. It f–ked me up for a while. It still f–ks me up. That was the start. Even though I played with fire in high school, that was the start.

“Like, ‘OK, this shit’s real. This shit’s got to happen. Now.”

When David Long Jr. finally returned from wherever he was hiding, he was a different person.

An angry person.

One “hamburger” drill planted a love for football. But post-Nikki, that love hardened into something more powerful. More embedded into his genetic code. Each time David Long Jr. buckled his chinstrap, he became more of a bull mowing down the nearest rodeo clown. Stuck on scout team the entire 2015 season, he served as a daily pain in the ass for all 11 players on West Virginia’s offense. Upperclassmen demanded he calm the bleep down, and he refused. He stayed in savage mode.

Both head coach Dana Holgorsen and defensive coordinator Tony Gibson would ask, plainly, “What’s wrong?”

Long replied: “A lot of people want it. Coach, I need it.’”

He didn’t open up to anyone about Aunt Nikki’s death. This urge to vanquish anyone and anything in his path consumed him.

“Y’all about to feel me every play,” Long says. “When I say, ‘I’m the man,’ I’ve got to live that. Walk that. Eat it. Breathe it. That’s why they were like, ‘Bro, you so serious.’ Why ain’t you serious?This shit is real. Life is real. It was deeper than just ball. They didn’t even know that the reason I’m whupping your ass right now is because I’m dealing with some shit at home.”

Holgorsen told Gibson that his starters could not block Long, so… hello? “Why are we not playing him?” he asked. The DC insisted a full year of development (i.e. feeding the beast) would pay off. Not that it was easy. It’s impossible to pinpoint one jaw-dropping moment because it didn’t matter if it was a random Tuesday in Week 10. Each practice, to Long, was a title fight. The redshirt linebacker made plays “every single day,” Gibson says, and his focus was freaky. He couldn’t turn it off. One night, all linebackers ate a home-cooked dinner at Gibson’s house and Long promptly devoured his meal, cleaned his plate, departed. He was in no mood to BS with friends or kiss a coach’s ass.

Right then, Gibson told his wife the kid was going to be special. Looking at his size, she was perplexed. (“Him?!”)

Phone calls back to Ohio helped through that torturous redshirt year. He’d chat often with one cousin. Curtis Boston, a.k.a. “Apple” — “App,” for short — kept Long patient and hungry. His roommate in Morgantown became a sounding board, too. But early on? Dravon Askew-Henry was understandably skittish. It took a while for the Mountaineer safety to earn Long’s trust. Those eyes were piercing.

“Crazy,” Askew-Henry says. “Laser focused. It’s like a bear. You don’t want to touch it.”

When he started getting scraps of snaps in ’16, this “bear” only craved more. To this day, Askew-Henry has never met anyone — in any line of work — who works harder than Long. And two days into June summer training, right when he was set to introduce himself to the nation, Long re-tore his meniscus. Deeper into the abyss he went. Mom visited for a full week. “Why me?!” Long asked repeatedly. Joyce tried to tell her son that all of this was happening for a reason and he couldn’t ask God “Why?” He sat in silence for two hours straight.

Mainly because he understood the stakes. At 5 foot 11, 220’ish pounds tape was all he’d ever have and now he was sidelined until at least October. Long vividly recalls being presented with two binary choices: Either stay optimistic or believe the “world is falling.” He chose the latter. He went “straight to all the negative shit” and depression was immediate.

One month later, life only got worse.

Cousins started dying. One by one.

On July 19, 2017, Dante Jones was shot and killed by his own cousin, Dwayne Marshall, on the 1200 block of Catalpa Drive in Dayton. Their mothers are sisters. The killing understandably rocked the family. West Virginia’s season began and — despite missing four games after knee surgery — Long finished with a team-high 15.5 tackles for loss. Then, more tragedy.

On Dec. 9, 2017, exactly 15 days before West Virginia’s bowl game vs. Utah, firefighters responded to the 2400 block of Central Parkway in Cincinnati. That’s where they discovered the charred body of “App.” No information was known then. His death remained a mystery until March 2023 when two suspects were charged for kidnapping, shooting and burning the 25-year-old Boston. Through the Mountaineers’ loss to Utah, Long lifted his No. 11 navy jersey to reveal a shirt he had designed as a tribute to “App.” He was in pure form vs. the Utes, with 2.5 sacks, yet also tore his labrum with one attempt of an arm tackle of beefy running back Zack Moss. This forced him to miss the spring of ’18 entirely.

“And then,” Long says, “I had another passing.”

On April 18, 2018, back in Dayton, Antonio Collins was found dead from multiple gunshot wounds inside of a blue car. He was 25.

The deaths ate at Long. To him, there’s a sharp difference between losing a family member and “someone you actually grew up with.” These were childhood fixtures. Long was close to Collins up to eighth grade and, upon moving to Cincy, he became extremely close to both “App” and Jones. Meanwhile, his brothers were still locked up. Long tried to maintain a relationship with them via JPay. The video-messaging service for inmates was only a cruel tease.

All of it only made him angrier and he took his pain out on the Big 12 as one of the best linebackers in the country.

In 2018, Long earned defensive player of the year in the conference with 111 tackles (76 solo), 19 for loss, seven sacks and four pass breakups. The Mountaineers went 8-4. The kid who didn’t say a word over dinner at Gibson’s house now talked shit all practice. All game. Even on random Sundays. From the couch, Long (a linebacker) told Askew-Henry (a defensive back) he’d embarrass him 1 on 1. Askew-Henry scoffed. Long demanded they head to the stadium. And right there on the game field, with an equipment manager playing QB, they battled in the 90-degree heat. “His competitiveness,” Askew-Henry says, “is through the roof.”

If this was the bear you do not poke in Year 1, Askew-Henry describes Long’s eyes as more “Undertaker” by 2018. That menacing stare was more intimidating than ever and, unlike the WWE, this was real life. Psychologists say it takes 3.5 seconds for one’s gaze to flip from acceptable to disturbing. Gibson would know. Whenever the coach held Long out of team scrimmages as a precaution, he thought his star linebacker just may ball up a fist and slug him in the jaw.

“He’ll stare right in your eyes,” Gibson says, “and stare a hole through you like, ‘Alright, I want to fight you. Don’t f–k with me right now. Don’t tell me I can’t scrimmage.’”

Long’s instincts were unlike anything Gibson had ever seen. The way he jumped gaps defied everything defensive coaches teach. Today at N.C. State, Gibson does not recommend his linebackers attempt to play this way. Back then? No way was Gibson reining him in. “He would just see a ball and go get it,” Gibson says. “He was so different.” Gibson points to a play vs. Baylor when he sent a corner blitz off the right edge and Long — with a slight delay — ripped upfield to smoke the quarterback. Most stunning was his raw strength. How Long steamrolled offensive linemen who had 100 pounds on him. Mid-conversation, Gibson texts a clip of Long pile-driving a Kansas State colossus into a running back.

“He was violent,” Gibson says, “and used every ounce of energy and strength from the tip of his toes to his forehead.”

And yet, Long enjoyed none of it. Long was “miserable as f–k.”

All success came at a cost. Death to death to death, sadness wasn’t the only emotion sinking Long further into depression. Knowing for a fact that everyone back home in Ohio was suffering, he became paralyzed with survivor’s guilt.

“An anxiety thing,” Long says. “I don’t even want to do certain things because I would feel like I was leaving them out. Even posting certain shit. I don’t want them to feel like I’m saying. ‘F–k y’all.’”

If he asked for help, Long thought he’d be considered a locker-room “cancer.” He told himself to suck it up. Joy was not an option. Long never took one day to appreciate the fact that those 6 a.m. ladder drills as a teen led to his Big 12 honor. When Gibson congratulated him, he shrugged. He stayed on — always. His heart needed to pound. His scope needed to be aimed at what’s next. Long admits he didn’t know how to turn it on and off. Mom could tell her son was hurting but Mom was also grateful David lived nearly 300 miles away from family members dropping dead. Anyone can get caught in this crossfire. Says Joyce: “He was placed away from that for a reason.”

So, in Morgantown, he became a loner. Long didn’t have a girlfriend and he refused to let his guard down to his closest friends, shutting his bedroom door and barely saying a word to Askew-Henry. One day, his roommate had enough. Askew-Henry started barging his way right into Long’s room and demanded his friend grab the controller for a game of Madden. Anything to snap him out of this funk… while still knowing all of this anger was also turning Long into a linebacker bound to play on NFL Sundays.

“He holds all of that in, which could be a bad thing,” Askew-Henry says. “He became a loner, but once he gets on the field? And puts on that helmet? You can’t stop him. That was his mindset. That’s how he dealt with it. David has that boxing mentality. It is you versus him. David is a competitor — that’s just in his blood. He comes from poverty. He comes from the hood. David’s got a little aggression to him that was already built.”

Adds Gibson: “Not a lot of people in the building knew what he was going through. He didn’t get close to a lot of people. He took care of business and kept to himself. He had a goal that he wanted to reach. He was on the mission.”

He measured small (5-11, 223) and slow (4.81 in the 40) at his pro day,a rough combination for any prospect at any position.

But these demons, for better or worse, were clearly a superpower. As much as modern NFL players are sold to the public as cyborgs — from the Combine’s lab-rat testing right into our fantasy-football lineups, gambling apps and All-22 breakdowns on social media — football is not won within an “if X, then Y” equation. These are grown men bashing into each other for three hours. For 17 games. Amid an ungodly amount of pressure. Find players built for such hellish terrain, and you’ll win. Ignore the person behind the facemask, and you’ll be fired.

Football challenges the mind in ways other sports never will.

Long knew he embodied exactly what makes this sport unique. This pain was worth it, he told himself. As draft day neared, he allowed himself to envision brighter days by mapping out a new life for everyone. Mom would quit her job. His brothers would get out of prison and they’d make up for 15 lost years. He’d extinguish that survivor’s guilt.

Surrounded by family in Atlanta, where Joyce now lived, Long expected to get drafted in the first or second round. His visit with Mike Tomlin and the Pittsburgh Steelers was a smashing success. He dreamt of himself following the team’s epic linebacker lineage, and then they selected Devin Bush 10th overall instead. Day 1 passed. Into Day 2, Long fully expected to hear his name called in the second or third round. He wore his best suit for the occasion. At No. 79 overall, the name “David Long” was announced, the room cheered at the sight of this name on the screen and those cheers quickly faded. This was the cornerback from Michigan who shared his name.

When a few asked Long if they could record him waiting for a call, he sniped “No!” Long ripped his jacket off and slipped back into world-is-falling mode.

The next day, he didn’t even bother getting dressed up for Round 4. Or Round 5. Or Round 6. Rather than see foolish teams select inferior linebackers who’d disappear from the NFL, Long went to his bedroom to take a nap and a call from one team woke him up. The Philadelphia Eagles said they’d come get him. Soon after hanging up, the Tennessee Titans then called to say he was their pick at No. 188 overall.

Holding a pretend phone, pacing around this room, Long relives the call. One family member peeked into the room and saw Long on the phone. Anticipation built. The pick became official and the house went bonkers. He celebrated… for one night. The next morning, Long defaulted right back to his natural state. “I really went f–king sixth round after having a defensive player of the year,” Long told himself. Anger only metastasized when he got to Nashville and coaches told him he’d be a special teams player. It was all harsh déjà vu.

Again, he went all-out in practice because Long viewed himself as the apex predator atop this food chain.

Vets knew they couldn’t screw with Long in training camp. Hazing never went beyond carrying pads.

With one exception.

Fed up with the rook’s Rudy Ruettiger antics, the team’s 6-foot-7, 309-pound renegade offensive tackle, Taylor Lewan, grabbed Long by the facemask after a play. Otherwise known as the universal act of disrespect. A skirmish broke out. The two were separated before punches were thrown. And from the sideline, Long paced. And paced. And paced with those Undertaker eyes glued to Lewan across the field. Sensing trouble, GM Jon Robinson approached Long and told him to keep his anger out here on the field.

He stands up to re-enact this movement, storming from side to side and, yeah, Gibson’s fears make a little more sense.

“I don’t take bullshit,” Long says. “It translates.”

His rookie year was a tease. Despite a breakout game vs. KC in the regular season and stuffing MVP Lamar Jackson on a key fourth-and-1 play in the playoffs, Long was relegated to backup duty. He hardly played in the Titans’ AFC title loss to the Chiefs and couldn’t understand why. (“That was my first time seeing NFL football.”) One month later, Covid-19 changed life as everyone knew it. But Long was getting good news. No, great news.

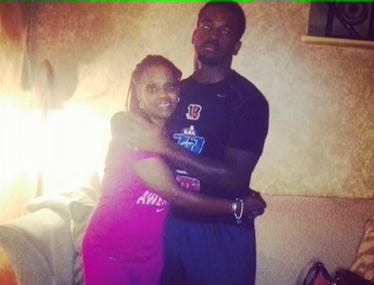

In November 2019, Deandre was released from prison.

In March 2020, Keith came home.

Fresh out of prison in Canton, Ohio, Keith sent David a video of himself holding a bag full of his clothes and as much toilet paper as he could jam in. “I heard y’all ain’t got no toilet paper!” Keith said. “I got all toilet paper!” David laughed his ass off. Most of all, David was relieved. He heard the Shawshank-like stories of inmates becoming institutionalized. When they’re free, they become paranoid. They cannot reassimilate into society. He feared prison could’ve permanently changed Keith. With the exception of those 1 ½ years on probation, his brother was behind bars from 2005 to 2020.

That single joke assured David that his big brother hadn’t changed one bit.

“Funny as hell. Laughing. That made me feel good.”

For eight months, the two made up for lost time. Best they could, anyway. David can count on two hands — “barely” — the number of times they saw each other in-person because on top of the government’s stringent Covid protocols, the NFL had its own mandates dictating players’ lives. The first week of November, the two turned a corner. Keith stayed over at David’s place on Friday, the sixth, ahead of a Titans-Bears game. For the first time since childhood, the two wrestled. Big bro quickly realized this wasn’t the same runt he used to ragdoll when David swung him so hard in the living room that it left a massive hole in his wall.

They said their goodbyes, and Keith headed to Atlanta to see Mom.

The Titans beat the Chicago Bears, 24-17, to improve to 6-2. Set to host the Indianapolis Colts on Thursday, they had a short week which meant driving to work at 7 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 9, 2020.

As Long pulled out of his driveway, he received a phone call from Deandre.

“Bro, you hear about Keith?”

He did not.

“They’re saying he’s dead.”

No, no, no. He didn’t believe it. No chance. This was a cruel rumor gone wrong. Click.

His sister called, and the news was true.

Less than one year after regaining his freedom, Keith Dewitt Jr. was killed.

He’s still shocked he drove 4 hours and 15 minutes without careening off the highway. How David Long Jr. managed to hold it together, he’ll never know. After exiting Mike Vrabel’s office in Nashville — still in tears — he drove directly to his mother’s house in Atlanta without listening to one second of music. He had no clue why or how Keith died and it’d take a long time for the jigsaw pieces to fit together.

Once the details materialized, the final picture proved more haunting than the family ever imagined.

Set to drive back to Nashville on Nov. 8, 2020, Keith got sidetracked. He stopped at a gas station and met four young women. Pent-up in captivity for half his life, this 32-year-old was obviously intrigued that they were intrigued. One particularly piqued his interest. So when the women invited Keith to Applebee’s, he was much obliged. He paid for their meals. “He’s vulnerable,” Long says. “Chicks want him to kick it? Let’s kick it.” It was all a trap. At some point, the women saw Keith had money on him, communicated the information back to their co-conspirators and lured him to the Upland Townhomes Apartment Complex in Mableton, Ga.

A neighbor’s camera captured the grisly scene in its entirety. David has never seen it. David never plans on seeing it. Only Joyce has watched the incident in full.

First, Keith’s car pulls up to an apartment. Two of the women exit.

Keith is on his phone next to his vehicle when two young men emerge from around the building and open fire. They shoot him four times in all.

Those two women dash into another car that speeds off.

One of the shooters tries getting into Keith’s car, fails, then approaches Keith — who’s still alive — and does not say a word. He swipes money from his pocket and leaves him to die. Perhaps Keith would’ve had a chance to live if an ambulance arrived sooner. He was able to (briefly) talk to police before bleeding out en route to the hospital. One of the bullets struck a main artery in his leg, while another struck a vein going to his stomach.

Mom is glad David never saw the footage.

“It is a lot,” she says. “I needed to see it to go on.”

To this day, the utter senselessness of this murder baffles the entire family. There was zero connection between Keith and anyone involved. Deaths past in the family were often fueled by retribution or street involvement. Not here. “Mindboggling,” Joyce says, “to this day.” The two shooters, Tyler Thomasand Kalvon Hinnant, received life with parole. They’ll be in prison at least 30 years apiece. Three of the women will be locked up for at least 15 years.One of the women flipped and shared the full story with authorities to receive a lighter punishment. Her sentence date is still pending.

After consoling Mom in Atlanta, Long headed back to Tennessee and played that Thursday night. The game was a blur. He was “seeing red” specifically on punt team vs. Colts linebacker Zaire Franklin. The two got into a hearty shoving match after one punt late in the third quarter and Long’s temper rose to an all-time temperature.

“You picked the wrong motherf–ker today,” Long muttered to himself. “I got something for your ass.”

The next punt, Long bailed on his blocking assignment (E.J. Speed) to ding Franklin and the result was disaster. Speed blocked the punt and Indy’s T.J. Carrie scooped it up for the momentum-changing touchdown. Vrabel implored Long to calm down on the sideline but even Vrabel must’ve known his request was futile. Tennessee lost, 34-17, and Long only inched closer, dangerously closer, to his personal breaking point. The very next day, he tested positive for Covid. Long woke up in sweats for four days straight and lost both 15 pounds and his sense of smell. To this day, he can only discern certain scents. All Long had to keep him company was his King Corso. No girlfriend, no roommate, no visitors. After losing one son, it pained Joyce to stay away. She wanted to be at her son’s side — virus or no virus — but this was also when Covid confusion reigned. Others convinced her to stay home.

Long was a loner (again) with nothing but dark thoughts racing 100 MPH. He overanalyzed that blocked punt, his football future and, above all, lamented the life he’d never have with Keith. Scrolling through his phone, Long realized he didn’t take one video with Keith over the previous eight months. So intent on living in the moment, Long never bothered hitting record for a keepsake. Hell, he hardly had any pictures. He wanted to hear his voice, but couldn’t even hear his voice.

“That’s where people go wrong,” Long says, “thinking you got time.”

Sadness soon succumbed to that familiar anger.

One question ran through his mind: “What’s next?”

He attended Keith’s funeral in a mask and gloves and thought of others, only others, telling Mom that the NFL offered mental-health services to families who lose loved ones. He passed along the phone number of a psychiatrist. “What about you?” she responded. Long insisted he was fine, nothing more, and football resumed Nov. 29 against those same Colts. Naturally, he delivered one of the best hits of his career. On a third-and-20 crossing route, he sent 5-foot-8 wide receiver DeMichael Harris airborne with a hard right shoulder and held up taped fists to reveal “L.L.K.” (Long Live Keith) and “L.L.A.” (Long Live Apple) written in marker. Because the NFL lacks a soul, this subtle alteration to his gameday attire prompted a letter from the league office. They informed him that this broke code. Whatever.

Again, Long reacted to death the only way he knew how. With foam-at-mouth fury.

Again, his physicality was football crack to everyone who had no clue what he was going through.

Long forced his way into the starting lineup, averaging 7.3 tackles per game with 16 TFLs in 22 games the next two seasons. The human wrecking ball also picked off Washington quarterback Carson Wentz at the goal line as time expired to win a game in ’22. Joyce knows those deaths hardened her son’s mentality for this unforgiving sport. “If you’re not mentally strong,” she adds, “it’ll do something to you.” Mom also knew son better than he knew himself. Joyce could tell he was “numb.” Eventually, Long took her advice and sought counseling. It helped.

A pulled hamstring sidelined Long the final five games of the 2022 season. All losses. Rough timing with the Titans falling out of the AFC playoff picture and unrestricted free agency on tap. Still, he saw the deals other linebackers were inking — Roquan Smith (five years, $100 million in Baltimore) and Tremaine Edmunds (four years, $72 million in Chicago) — and expected to cash in.

Like draft day, he made the grave mistake of getting his hopes up.

His market wasn’t only lukewarm. It barely existed. Reality did not match everything he mapped out in his mind because, this time, teams didn’t trust Long’s hammy. His agent, David Mulugheta, said the Denver Broncos were pleased with Josey Jewell. The Seattle Seahawks were fine with Jordyn Brooks. The Las Vegas Raiders weren’t interested. (“I’m like, ‘Get the f–k out of here!’ I’m pissed. There’s no way.”) Strays from his own head coach likely factored in. Two months prior, Vrabel referenced Long as one of the team’s “repeat offenders” when it came to soft-tissue injuries. Bizarre considering you never hear head coaches publicly criticize players on the verge of free agency and, uh, Mike? This was also a player who enthusiastically launched himself into harm’s way. Repeatedly.

“You see me play with my hair on fire,” Long says. “I could see if you say that about the guy who’s an asshole, who shows up late, who doesn’t really take care of himself. I’m never that guy.”

After staying mum all offseason, the Titans got around to offering Long a one-year deal that Long interpreted as a five-finger slap across the face.

The Dolphins offered a modest $11 million over two years and he admittedly wasn’t thrilled about this deal, either. Not after putting in “endless” work to get to this point. But from his offseason training spot in Austin, Texas, Long told Mulugheta that apparently he hadn’t done enough yet. He took a day to pray, and said yes to Miami. Chose to join cornerback Jalen Ramsey and others to chase a title in South Florida. After signing his contract, he flew right back to Austin for grueling, self-induced two-a-days.

Anger never activates pity.

He never claims to be a victim.

“I’m like, ‘Alright, ‘f–k it. We’re going back to work man,’” Long says. “I’m in that bitch working.”

His first night of fine dining in South Florida, Long ate at “Gekko,” a Japanese steakhouse owned by rapper Bad Bunny. The team’s new linebacker polished off his plate and — to his shock, for the first time — he was not stricken with a shred of guilt. He didn’t feel bad that his kin back in Ohio couldn’t enjoy a meal like this.

A strange, new emotion crept in.

Joy.

Friends no longer pry David Long Jr. from his bedroom to play Madden. One year into life with the Miami Dolphins, he’s a renaissance man.

A sampling…

- He learned how to play tennis. And golf. And… piano? That’s next. As a kid, Long had romantic visions of playing the piano for his future wife. One day, he woke up and searched for an instructor in Fort Lauderdale. Lessons start soon.

- He attended the F1 race in Miami.

- He rode a bike 54 miles with Hall of Fame linebacker Zach Thomas for the Dolphins Challenge Cancer event.

- He watched the Florida Panthers’ Game 7 triumph over the Edmonton Oilers live from a suite.

- He’s into art. The linebacker will soon meet “Surge,” a local artist whose “postgraffisim” is splashed across South Florida.

- He’s running his foundation, “Not Long Ago,” to help single mothers and kids alike. The plan is to build an after-school program back in Cincy, one equipped with a music studio.

- He’s reading more than ever. Two books changed his look on life: “The Four Agreements” by Don Miguel Ruiz and “The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment” by Eckhart Tolle. (He was fully enlightened.)

- Like Mom, he’s into crystals. (“An energy thing. There’s something to it.”)

- He changed his number from No. 51 to No. 11.

- He has a girlfriend. They met on Instagram in January, hung out for her birthday weekend in March, took a vacation to Turks and Caicos and things are getting serious. She just hung out with the whole family on a getaway to their Gatlinburg cabins. They had a ball zip-lining.

- He feels no shame posting anything on IG. This past Wednesday, Long shared a pic of himself holding a bottle of Caymus Cabernet Sauvignon.

- He’s going to become a pilot. After meeting one from Italy, he was sold. “Coolest dude I know!” he says. “Let me show you.” With that, Long pulls up pics on his phone. One teammate told him he can get his license in three months. Long will navigate the skies soon.

“Why not?” he asks.

When Keith Dewitt was murdered and his world was falling worse than ever, Long woke up one day and decided he was sick of sulking. He thought back to how Keith stayed upbeat through his wretched life behind bars. Maybe he didn’t have a tangible video on his phone, but David could clutch to memories. If anyone should’ve been drowning in dread, it was Keith. On calls from prison, he’d never mince words. “What are you down about?!” Keith would tell family members. “Shoot, you’re out in society!”

This time, Long actively chose the optimistic option.

Of course, one eureka moment of discovery is too cinematic. Not realistic. The only way David could change was if his habits changed. He became determined to live with intention and create new “muscle memory.” It’s no shock the next book on his reading list is “Atomic Habits.” This 3 ½-year transformation has been gradual, and there’s no finish line. The key wasn’t consciously picturing those two distinct paths in his head one time.

Rather, all day long.

With adversity big and small.

“Every day you have a choice,” Long says. “Something happens to you — how are you going to handle it? I was picking the other one. I was picking the sky is falling. In the morning, something happens. You have a f–ked up morning. You burn your toast. Spill your coffee. And you’re like, ‘Ugh. It’s going to be a bad day.’ Or it’s like, ‘OK, cool. That’s that. Looking at everything more in a positive light and it’s a choice. It is: How strong are you mentally to make that and keep it? You can fake it: ‘Oh, it’s nothing.’ But when you’re in the car, traffic is pissing you off. You’re still pissed from the morning.

“You can never undo it. It’s all about perspective. I’m choosing to look at it a different way.”

Bad news is a guarantee. His father, David Long Sr., is currently behind bars for trafficking cocaine. Another cousin died on New Year’s Day this year. Even Keith’s problems linger to this day. The family’s been embroiled in a legal battle with a Dayton cemetery for burying him in the wrong location. He still doesn’t have a headstone. Long now realizes he cannot carry the burden of it all. His day-to-day emotions cannot be a direct product of the day-to-day troubles of all suffering back home because, frankly, “there’s no escaping the bullshit.”

This life breakthrough will now feed a career breakthrough in 2024.

First, understand that Long hates coming off the field. Back to little league, he’d clown anyone who tapped their helmet to sub out. That’s what made the first month of the ’23 season under Vic Fangio so infuriating. All of the DC’s rotating of linebackers made him feel like a shooter in basketball unable to find a rhythm. In a 42-21 win over Carolina, Long finally found his stroke with 11 tackles and a harpoon of a (completely legal) hit to the rib cage of No. 1 overall pick Bryce Young. That point on, Long was a sign of a hope on a MASH unit of a defense thrifting for senior citizens on the waiver wire to rush the passer by January. Players were thrilled to see Fangio depart, he confirms, and the energy under new DC Anthony Weaver has been refreshing. We can expect relentlessness.

Now, Long will wear the green dot on the helmet. Long will relay all play calls.

“You’re the leader of a war,” he says, “like the 300 Spartans.”

Long is the general, the player who’ll scream “Prepare for Glory!” and make America respect a franchise that has shriveled in January.

The defense now takes on his personality.

“When I’m the head of it,” Long says. “I can take the blame for anything. Like, we weren’t good vs. run this week? I can take that. I want that. You can allow me to be who I am and, whether it’s a win or a loss, I’m able to take those losses. Like, ‘Coach, that ain’t them. It’s me.’ That’s what comes with that position. But it’s going to be a reflection of me. If we’re out there flying fast, I am telling them before the play, ‘Y’all better beat me there! Somebody better pop it out, because I am.’”

Teammates are eager to rally around him. With each hit last season, Long started talking more last fall. Defensive tackle Zach Sieler remembers many moments when the Dolphins defense was gassed at the end of a long drive and one Long blast re-energized the unit. His fearlessness to detonate an “A” gap to smithereens has a contagious effect.

“He’d come down and put a boom on somebody,” says Sieler. “It was really cool to have that and just see him go crazy.

“You hear it or you see it and it makes those next few plays that much more powerful. You get that momentum back. Having a linebacker who can come downhill and do that and is willing to do that is just incredible.”

Sieler never knew about Long’s past. He’s speechless when details are shared.

Those who do know Long best see a 180 in the man. Gibson texts his former linebacker often and makes a point to FaceTime him on Oct. 12 every year. They share the same birthday. Long “is having the time of his life,” he says. Last November, out of the blue, Long called Askew-Henry to say he was in his college roommate’s hometown, Pittsburgh, and was going to pop in to hang out. The two sat on the couch and chatted for at least three hours. This was a completely different Long than the one from Morgantown. “You miss me or something?” Askew-Henry asked.

“He was ear-to-ear smiling,” the DB says. “It just seemed like he had less off his shoulders. He was more at peace.”

To Mom, he’s more outgoing. More excited about life itself. Forever suspicious of new friends, Long is determined to meet new people. Says Joyce: “I love that for him.”

Of course, this all begs one uncomfortable question.

Anger battered his mental health. Anger also made Long one of the sport’s most ferocious competitors. Can he manually shut the rage on and off? As Long taps those piano keys and takes up art and bares his soul to this new girlfriend, it’s fair to wonder if he’ll still summon the beast within three hours each Sunday. Long’s edge has been a blatant disregard for consequences, a sadistic affinity for those weekly car crashes. As the snarling middle linebackers we all grew up on go extinct, he’s the hostile throwback. A direct product of trauma.

Everyone may sense a cheery David Long Jr. these days, but Mr. Rogers… this is not.

This linebacker spiking every third sentence with expletives will not change.

When our conversation shifts to the NFL’s latest attempt to soften the sport — the banning of the “hip-drop” tackle — Long turns disgusted. Admits he nearly tweeted, “I’m going to just knock y’all helmet off,” before correctly realizing that’d get him blacklisted. To him, the commish and owners made up this term in an attempt to slow down defensive players. His solution: “Go right through y’all.” You’re only pulling a ball-carrier down from behind if they slip past you. This offseason, he loaded more plates onto that barbell to get stronger and stone backs in their tracks. Even after suffering a scary concussion vs. Philly last season, colliding head-first into a teammate, Long does not plan on diluting his game with a millisecond of caution.

Whatever happens on the field, he asserts, is meant to be.

He’ll fully sacrifice brain and body because he’ll never forget Mom telling him seven years ago to never ask “why.”

“This is my job,” Long says, “and I’m already accepting whatever comes with it. I’m here for a way bigger reason.

“I have some pain in me to get it, but I’ve grown to not make it who I am.”

In that “bigger reason” a work-life balance can exist. Anger and joy are one and the same each collision. If anything, Long will play with more fire because of everything that’s happened. Anything less is a disservice to Aunt Nikki, Keith, his cousins and anyone in his family who may be flirting with death. His 1,000 snaps this season are 1,000 salutes to them all. Faith is central to his awakening. Long used to hate saying prayers before dinner with a large group of people. The exercise felt empty. Now, the words translate to his life. He reads a devotion each morning and carries a Bible with him all day.

He isn’t ignoring the trauma, isn’t gauzing the pain with distractions. This is about viewing those deaths through a “positive light.” A massive portrait of a smiling Keith Dewitt now greets him every time he enters his home. A few pictures in his phone help, too. That hole in the wall, timestamped at Nov. 6, 2020 at 3:54, still gives him chills. A ribbon tribute to Aunt Nikki is tattooed on his shoulder. And the NFL’s suits can get bent. He’ll continue to inscribe LLK and LLA whenever he wants. (“I don’t give a f–k about the fines.”) For the longest time, he refused to even talk about the events that led to Keith’s death. Not anymore. Deandre is rebounding, too. He lives in Columbus, Ga., with a wife, a new baby girl and a steady job driving trucks.

Whenever news of the next death lights up his phone, David won’t be alone. For a man who admittedly loves hard yet moves fast — “I ain’t got time to waste!” — it’s safe to say he’s mulling the next step. When he got back from that trip to the Turks and Caicos Islands, Long never felt better. He told his best friend he can “see.” When his friend asked for clarification, he simply added: “My vision. I can see clear.”

That’s the case today in Florida… until the final five minutes. He imagines the life he could’ve given Keith with just a portion of his contract and his voice turns somber.

“That’s the most f–ked up part about it. I didn’t get to experience life with him.”

Free in March. Dead in November.

“Gone. Forever.”

Then, Long catches himself. He taps his cell phone to show that picture of Keith in his house. The sunglasses. The pearly whites. Keith’s gregarious smile makes him smile every time. In the next breath, Long says how much it helps sharing his life with everyone. This is therapeutic. He hits play on a video of himself looking at the portrait. “That’s my dog,” he says in the clip. “Big bro, man. Keeps the house safe and glorious.”

David Long Jr. is at peace with all of the lives lost.

Now, it’s time to start living his.