Jason Taylor signals to his teammates during a game in 2011. Those fingers endured more than a few dislocations during his NFL career. Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images

Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images

When Jason Taylor played professional football, his name struck terror into opposing quarterbacks. Now that he’s retired, that name may soon adorn a plaque in the Hall of Fame.

For a reason why, look to seasons like the one Taylor had in 2006, when he was playing defensive end for the Miami Dolphins. He was named the NFL’s Defensive Player of the Year that season, racking up 13.5 sacks, recovering two fumbles and even returning two interceptions — quite a feat for a lineman.

Jason Taylor signals to his teammates during a game in 2011. Those fingers endured more than a few dislocations during his NFL career. Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images

Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images

When Jason Taylor played professional football, his name struck terror into opposing quarterbacks. Now that he’s retired, that name may soon adorn a plaque in the Hall of Fame.

For a reason why, look to seasons like the one Taylor had in 2006, when he was playing defensive end for the Miami Dolphins. He was named the NFL’s Defensive Player of the Year that season, racking up 13.5 sacks, recovering two fumbles and even returning two interceptions — quite a feat for a lineman.

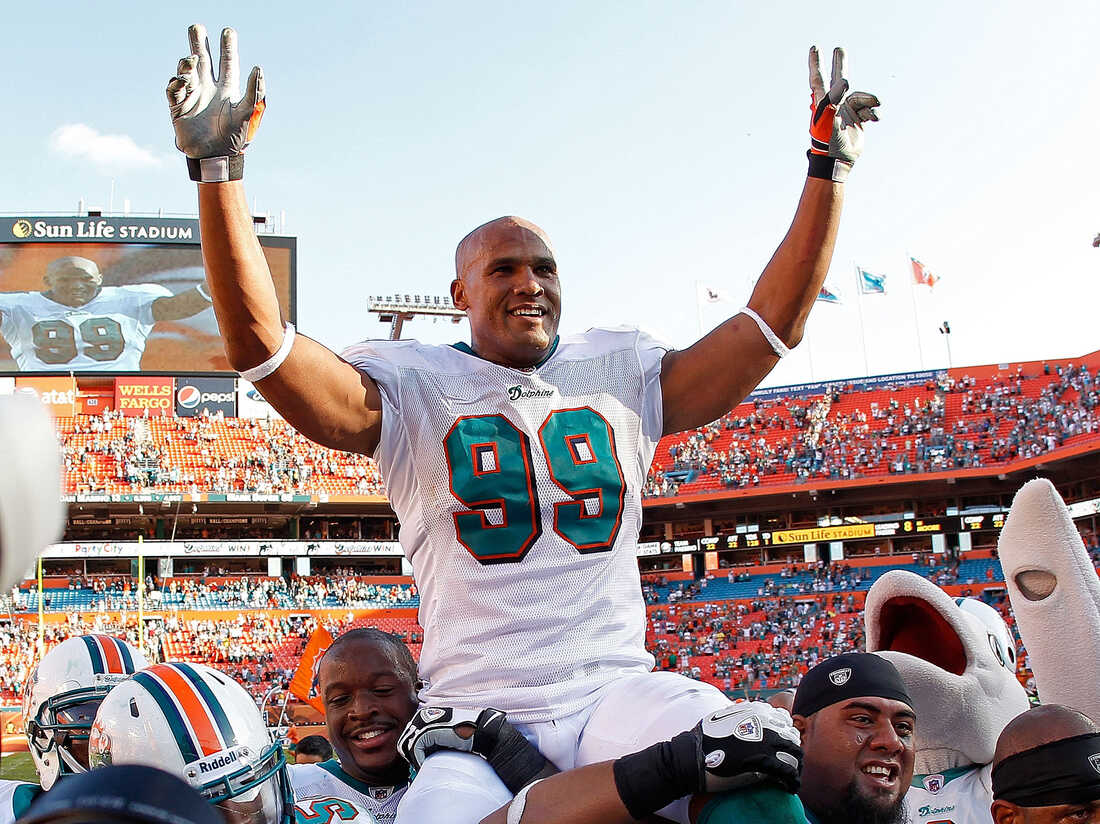

Taylor spent the bulk of his career as a Miami Dolphin. After his final game in the NFL, he was carried off the field by teammates. Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images

Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images

In that same year, though, he also played through a gruesome spate of injuries. In his own words: “A bad back and broken right forearm; tore both plantar fascias; multiple dislocations on fingers, thumbs; broken collarbone; … MCL [medial collateral ligament] sprain several times.”

He also suffered from compartment syndrome that year, a condition in which internal bleeding causes pressure to build upin one of the body’s “compartments” — either an arm or a leg, or another enclosed space in the body.

In Taylor’s case, it was his left leg. The injury led to 9 inches of nerve damage, a staph infection and 10 months of terrible pain. At one point, doctors even warned that Taylor might need surgery to remove his leg entirely. Luckily, he avoided amputation; it was still his worst injury in a 15-year NFL career.

Just one of those injuries would cause the average person to take some time off work. But Jason Taylor is not your average person. He tells NPR’s Audie Cornish how playing through such pain has become ingrained in the game of football, and how bearing it is often necessary to keep a job.

Interview Highlights

On why it’s difficult for football players to admit when they’re hurt

Everybody’s hurt. That’s what you have to understand: Everybody’s hurt. The day you play football will be the last day you’re pain-free. It’s a physical game; you’re going to be hurt. But being injured and hurt are two different things. …

On “manning up” and playing through pain

It’s part of life. I mean, when you sign up to play a game like football, you have to deal with certain things and a certain level of being uncomfortable and a certain level of pain. …

Some guys have higher pain thresholds than others. I’ve always been a guy that has a high pain threshold and also refused to accept not trying, or losing, based on being uncomfortable or in pain. I probably have a bit of a twisted outlook on playing through things like that, but everybody’s different.

On concealing a catheter in order to play

It probably wasn’t wise, medically. The doctors weren’t happy about it, but I prided myself on being there every week, playing at a high level, and was hard on myself when I didn’t. I wasn’t going to let a catheter … hinder me, if at all I can get out there and do it.

On notions of masculinity in football

There’s probably an antiquated view on that by some guys. As medicine has changed, as the attention on concussions and … such has changed in sports, I think people are taking a more educated look at treating athletes, and the way they kind of program athletes into thinking that if you sit out because of an injury, you’re soft. Was that kind of thinking around before? Yes. Is it still around nowadays? Yes, in some ways.

But [sitting out an injury] doesn’t make you less of a man. It means maybe you have a lower pain threshold; maybe you just aren’t willing to push yourself through it. And that doesn’t make you less of a man. It might make you a different type of competitor. It might make you less intense than some guys, but it doesn’t make it wrong.

I’m good. I’ve got nothing lingering right now. Am I 100 percent comfortable every day? No. There’s things that nag a little bit. You know, joints don’t bend as much as they used to. Hopefully I won’t have any major issues in the future, but we shall see.